¶ Introduction

Weather conditions vary considerably in cold climates. Winter weather is often very changeable; pilots may give out good reports in VFR conditions and some minutes later VFR may not be possible.

Remember, mountain flying and bad weather don't mix.

When penetration is made of a snow shower, the pilot may suddenly find himself without visibility and in IFR conditions. The pilot's visibility range is reduced in these conditions and there are no contrasting ground features.

The weather can create some effects to the aircraft structure that impact the safety

¶ Categories of carburetor ice

There are 3 categories:

- Impact ice - Formed by impact of moist air at temperatures between -10°C (15°F) and 0°C (32°F) on airscoops, throttle plates, heat valves, etc. Usually forms when visible moisture such as rain, snow, sleet, or clouds are present. Most rapid accumulation can be anticipated at -4°C (25°F).

- Fuel ice - Forms at and downstream of the point where fuel is introduced, and occurs when the moisture content of the air freezes as a result of the cooling caused by vaporization. It generally occurs between 4°C (40°F) and 27°C (80°F), but may occur at even higher temperatures. It can occur whenever the relative humidity is more than 50%.

- Throttle ice - Forms at or near a partly closed throttle valve. The water vapor in the induction air condenses and freezes due to the venturi effect cooling as the air passes the throttle valve. Since the temperature drop is usually around -15°C (5°F), the best temperatures for forming throttle ice would be 0°C (32°F) to 3°C (37°F) although a combination of fuel and throttle ice could occur at higher ambient temperatures.

In general, carburetor ice will form in temperatures between 0°C (32°F) and 15°C (59°F) when the relative humidity is > 50%. If visible moisture is present, it will form at temperatures between -10°C (15°F) and 0°C (32°F).

¶ Carburetor heat

To PREVENT carburetor ice, a well used system is the carburetor heater.

The critical phase of flight regarding carburetor icing is the descent, because a high flow of air is cooling the engine which is not self-heated due to the power reduction. In order to heat the air coming from the flow and entering the carburetor, the carburetor heater was created.

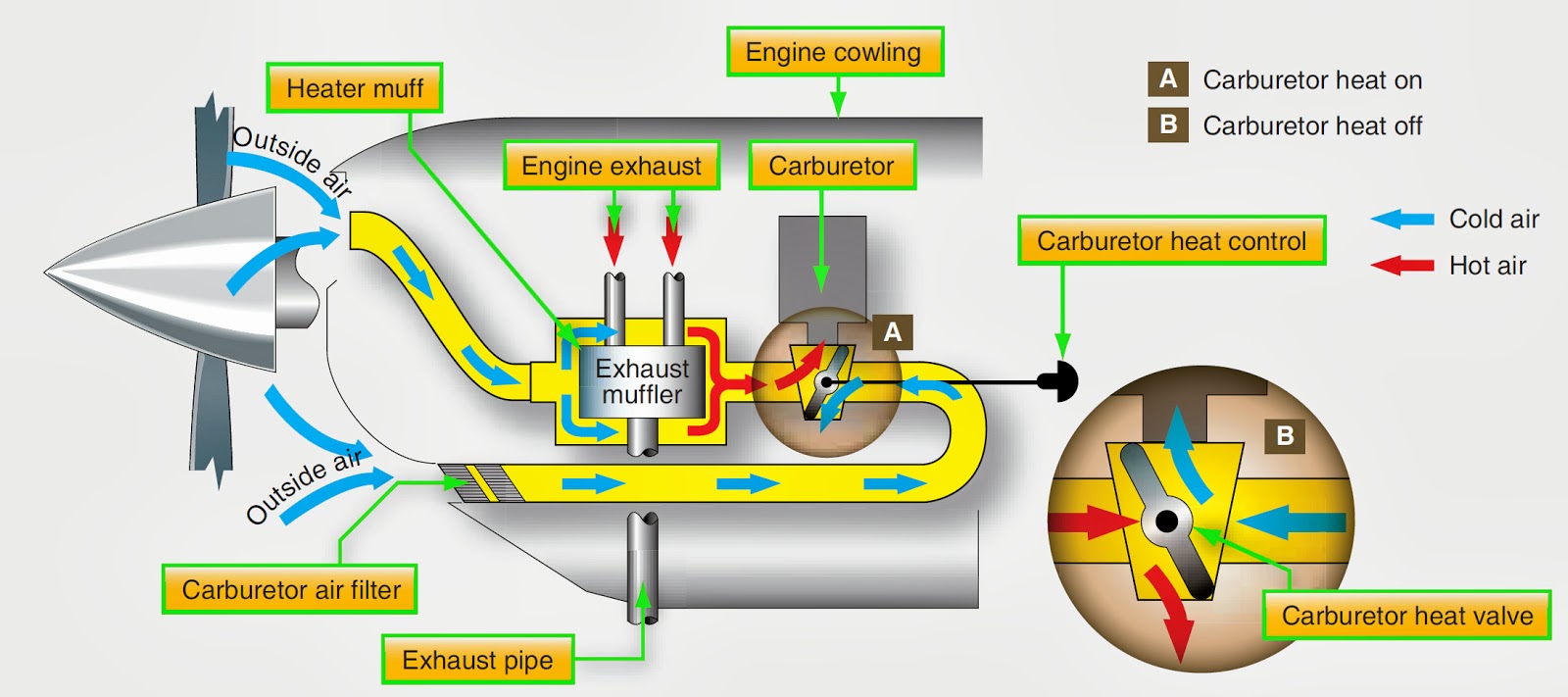

As you can see on the picture above, in stead of taking air directly from outside, air is taken around the exhaust pipe, in the exhaust muffler. The air is now heated and PREVENTS carburetor ice. This does not act as deicing, because if ice is created on the throttle valve, venturi effect will be reduced, and even when the carburetor heater is activated, it may take a long time for the ice to melt.

Caution! Except for engine testing, the carburetor heater MUST NOT be activated on the ground, because the air filter is bypassed; elements like pebbles or sand could enter the carburetor which could be very harmful.

Carburetor heat reduces the engine power ! When activating the carburetor heater, air entering the carbutetor is heated. Hot air is less dense, so the mix is richer. If the mixture will be too rich, the engine power will decrease.

Normal value for aircraft piston engine testing when activating the carburetor heater is a loss of 100/150 RPM at 2000 RPM.

A carburetor air temperature (CAT) gauge is extremely helpful to keep the temperatures within the carburetor in the proper range. Partial carburetor heating is not recommended if a CAT gauge is not installed. Partial throttle (cruise or letdown) is the most critical time for carburetor icing. The recommended practice is to apply carburetor heating before reducing power and to use partial power during letdown to prevent icing and overcooling the engine.

¶ What the pilot shall do

To prevent carburetor icing, the pilot shall:

- Use carb heat ground check

- Use heat in the icing range

- Use heat on reduced power (approach and descent)

The pilot should be aware of the warning signs of carburetor icing which includes:

- Loss of RPM (fixed pitch)

- Drop in manifold pressure (constant speed); rough running

Pilot shall respond to warning signs by:

- Applying full carb heat immediately (may run rough initially for short time while ice melts)

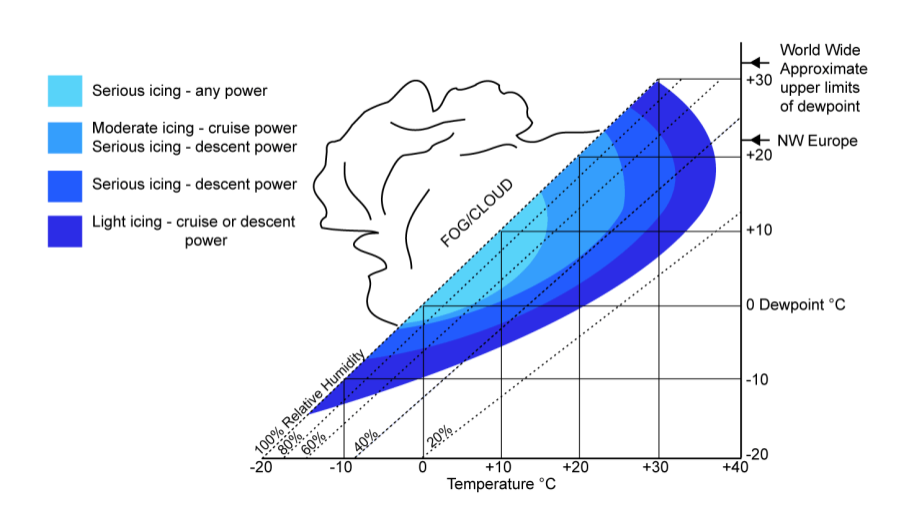

In the chart below, the curves encompass conditions known to be favorable for carburetor icing.

The severity of this problem varies with different types, but these curves are a guide for the typical light aircraft. Light icing over a prolonged period of time may become serious. When you receive a weather briefing, note the temperature and dewpoint and consult this chart.

¶ Conclusion

When flying a piston carburetor engine, the pilot should really pay attention to air relative humidity. A carburetor is still present on most of the current piston engines, they are all equipped with a carburetor heater. This system really needs to be used when reducing engine power in order to prevent carburetor icing.

Latest aircraft (especially high-power ones) are equipped with injection piston engines, which solve the problem of carburetor icing and reduce (not completely...) the probability of engine icing.

- FAA Safety : Winter Flying Tips - P-8740-24 (1996)

- VID 450012 - Creation

- VID 496402 - Wiki.js integration